M.L. BLACKBIRD

~ A Wish Too Dark And Kind ~

CHAPTER THREE. THE OLD PRINCE’S PARTY

The fireplace was lit and ready to consume his life, or, at least, the memories of what it had been. Roman had waited for this day for so many centuries, and now?

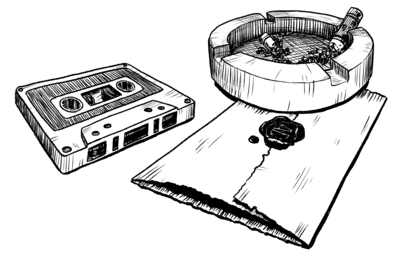

That piece of paper, that invitation, didn’t want to leave his hands and, instead, kept moving in them. The letters, piled on the table beside the armchair, stood there too, looking at him, scared of the fire but not bothered by how hard this was to him. The invitation was proof his time had come at last.

This was how his end started. If so, he wanted to go unhindered, and burning all the letters to his dead sibling seemed the best way to get rid of any burden. Those letters were the only thing he still cared about. He had to burn them.

Roman picked up the first one. His memories didn’t weigh as much as he thought. His eyes followed the paper as it flew into the fire. It talked of his betrayal. Just like Cain, murderer and betrayer of his own brother, only one thing he feared for almost half of a millennium: dying. He chuckled at the irony.

With the letter, pain, guilt, and neglect went up into smoke. All those emotions, caught in paper, twirled in a gray cloud over the fire that called him by his name. All those stories gone and, with them, that infant left in front of a church, the drunkard father, and his lonely death—stabbed, suffocated in his own filth—such a relief.

One letter gone, many others still to burn. A long process he savored. The pain of taking out that tooth had left him with the pleasant feeling that his suffering, his real suffering, was behind him. A second letter flew into the fire, and again, Roman felt the same pain.

If a new world, even a better one, had to come, it must do so through screams and pain. No birth arrived without pain and blood, and the memory of the sea of blood in the prince’s eyes was Roman’s last memory of him.

The first time Roman met the prince, it was amid a crowded party in Paris. The old man, the prince, could go through it unnoticed. His gray hair, small body, and face, one out of many, were built to be forgotten. Roman met him as the prince came down the stairs of his palace. “Old friend” the prince had called him, and to this day, Roman still didn’t know why he had received such a salute.

He had lost himself searching in those icy eyes, as he had seen something behind them. The eyes of someone else who had died alone many times. Someone old who had escaped the world many years before. Those eyes called him old friend, but whose eyes were they? Those of the man who stood in front of him or those of a monster who stared at him without a shred of light?

He would die because of that man. He had seen the sea of blood in which the monster was swimming. Roman would spend years swimming in there himself.

Now that invitation.

The wolf quivered within his guts—everywhere within him—chained for so long that it yearned for the day it would be free to drown in its fury. Nothing mattered anymore. And yet, fear took hold of him. Dread that the prince might be a monster far worse than he was himself.

Roman closed his eyes and reached for the flame where his letters were burning, and the fire, driven by a higher intelligence, tried to reach him. And perhaps, who knew, the best end would have been to burn by the fire. The wolf winced. For the beast, no time would ever be a good time to die.

He threw another letter into the fire.

His centuries whispered into his ears, talking of nasty and mysterious things, of caverns and wars, worlds above and below, philosophy and magic. A rant of fire and smoke of which, after so many years, he could barely hear the words but not understand the meaning. They talked of arcane knowledge, worlds beyond this world, keys and doors, rituals, sacrifices, and monsters from before his own long story.

“Enough,” he said, gripping the armrest.

The fireplace stood in front of him, silent now, just barely crackling. No words or whispers.

The pile of letters almost gone, he threw the final paper into the fire and stood to look at the last words on it burning. A name, one he had chosen, Azurine. And with it vanished, he was finally ready.

***

The fire had gone out, but Roman stood there watching its cinders. He took the phone and called the only number saved in it. “I’m ready, sir. It is all done.”

“We are in luck,” said a hoarse voice. “We spotted the target in Paris.”

Roman’s fists clenched so much his knuckles whitened. Despite the centuries he had spent in the order, Roman had never met the high priest in person and knew only his hoarse voice, his face always hidden behind the shade of a confessional or the handset of a phone. Even so, the high priest had been a father to him, much more than his real one had ever been. It was the high priest who had given him a mission, a target, and with it, purpose.

“Listen,” the voice kept going, “help with the search. I want you to catch the target before the party starts. The others will take over from where you leave off, but we can’t let that man have it.”

“I will make sure it won’t happen,” Roman said, his teeth grinding against each other.

“Then, all the best, brother Roman. Stay under God’s wings.”

“Always under God’s wings.”

***

Evidence J-0006 to the investigation I-7242

Extract from Arnaud Demeure’s journal

13 July 1258

Hurt, scared, and hungry, this is no place for me. If only Father were here, in this cold, ugly house, he would teach them how to treat a noble of France. But he is not here, and the day will come when I won’t need a father to give them a lesson.

***

The old cassette’s noise had filled the room. Finding one of those old players had been harder than Hermann thought, but at the end, he was there, in an old motel with carpets the same color as rats that smelled a bit of rat too. The warm tobacco flavor that lingered in the air was a sweet distraction from that reek.

Valentine, his sire, had demanded a swift job, but the tapes meant more to Hermann than they did to her. It had never been easy to understand her intentions, and this cleaning job, as she had called it, was even stranger than usual. Valentine had been stranger than usual herself since the moment she had received that letter from Paris. She hadn’t let him read it, but her face when she saw it was that of someone uncertain about which direction to take. A face Hermann had never seen on her.

As he spent his time sticking newspaper to the windows, an old man’s voice and that of a young boy took turns speaking out of the cassette.

“Nice to meet you, Hermann,” said the old man’s voice. “Your mom and I talked about you at length. She is proud of you. She said you are a bright student. How is life at school? Are you making lots of friends?”

“No more, no less than the others, I guess,” said a youthful voice. “Most of my friends are on my softball team. All good, anyway.”

“Softball, that sounds interesting! And you have a team, you say?”

“Yeah, I’m the captain,” said the young boy with pride in his voice. “First in the league but going up and down from second. We might win this time.”

Both voices disappeared, replaced by the striding noise of the tape moving in fast-forward.

Hermann pushed play.

“Dr. R.J. Millard, 27 August 1978,” said the same old voice as before. “This was my first visit with Hermann Walker. These are the notes at the end of my session. Hermann is a polite kid, studies hard, and his mother describes him as having a normal ability to interact with others and make friends. Hermann has been through therapy before, one or two sessions after his father’s death.

“According to his mother, he is one of the best students in his class. She says he is a well-mannered and methodical kid. After having met him today, I can’t say I disagree. There is something that bothers me, though. I’m not sure if it is the way he speaks, the way he moves as he talks, but there is something, for lack of a better term, unnatural, about this kid. The whole time I sensed he was hiding something.

“His own mother sent him to me for this very reason. I wasn’t sure of what to think of a mother that brings a fourteen-year-old boy to me without a clear motivation, but now, I admit, the whole thing is fascinating. But I’m an old man who is too easy a prey to his curiosity.”

***

“Same dream again?” Millard asked.

“Yeah …”

A creaking noise came out of the tape. Doctor Millard leaned on his armchair every time Hermann talked about his dreams. “Would you mind telling me about it again? Anything new you noticed?”

“Nothing too different from the other times, Doctor. I’m bouncing up and down in slow motion. Beneath me is a man. I have no idea who he is. And behind him is a woman. I know her, or at least myself in the dream knows her. She floats behind him, naked and surrounded by light. She brushes her hair as it falls on her back. She turns and smiles at me. Then nothing; it’s dark and something shrieks. I always wake up at this point.”

“And what do you feel when you wake up?”

“Nothing too special. Nostalgia, I guess.”

***

The time was passing fast as Hermann listened to the tapes. He found some entertainment in listening to them. His entire story danced in the motel’s putrid air, while outside of his window a man was puking his stomach out and another shouted at the traffic.

“You are quiet, boy,” said Doctor Millard from the tape. “Did you miss some sleep?”

“Yeah. I keep having the same dream and that stupid nightmare.”

“What kind of nightmare?”

“I don’t know, people shouting. Light shines behind a glass, a window. I don’t know, a fairy or something? A sphere of light traveling at a crazy speed and nothing after. It bumps against the glass, and there is a crash. After, it’s just yelling and a lot of red all over. I guess they are shouting a name. I’m not sure who they are calling. All around is a white light that wraps me, and I shine all over.”

“And?”

“Nothing, Doctor. Nothing. I wake up after that.”

“I see,” Millard said, his scribbling so furious it came through the cassette. “What name are those people calling? Your father’s name?”

Hermann stood on his feet that day, he remembered. Not that he didn’t want to talk about his father, but Millard just could not stop with it. “What does my father have to do with all this?”

“Hermann, your father died in a car accident. Do you still hold a grudge?”

“I think he should have stuck around just a little more, but no, I wouldn’t say so. I’ve managed.”

***

The tape shrieked again as he pushed fast-forward.

“Is it already time? Are you sure about it?”

“Yes, Hermann,” said Doctor Millard. “We spent at least one hour today trying to carve out something from you, but despite the time, I don’t think you want to trust me. It’s been ten years, and you still can’t open up to me.”

“I don’t get the point, Doctor.”

“Okay, let’s try again. Can you explain to me why you need to spend your days with your nose in books? Why do you need to win every game you play? Why at all costs?”

“What’s wrong with it? I mean, that’s what she … I mean, what my mother always wanted. Is there anything wrong with it?”

“Hermann, we are done for the day. I’m tired. You are frustrated. Let’s move this discussion to another time, okay?”

***

“Doctor R.J. Millard, 27 August 1989. Last session with Hermann Walker. This day, eleven years ago, a fourteen-year-boy entered my office for the first time. Today, a twenty-five-year-old man came out instead. A man who has spent the last eleven years in therapy. He is like a son to me, and the biggest mystery of my career. I can’t stop being obsessed with his way of speaking and the way he moves. There is something in the way he sees things, and perceives the world around him, such a level of depth and speed that I can’t follow.

“He has built a character and a plan for his life I can’t understand, or maybe he just doesn’t want me to understand. As if something or someone bigger than him talks from the shadows, and he puts effort into hiding it as much as he can. But he can’t hide the thirst and hunger he has for the world. Such hunger that he might swallow it whole. His mother’s death has worsened this further, and as she disappeared from his life, another woman entered it. He talks of her as one would talk of an old friend who came back from a lifelong travel.

“In a short time, she has gained more and more of a grip on him. I am not sure if this is a healthy relationship for someone like Hermann. From him, no real attachment toward a partner. She is more like a mother figure; an attraction toward opportunities he can’t describe. On her side as well, from the way he talks of her, the pushes are toxic. He might not understand it, but she has a plan for him, I am sure of it. Maybe the surprise of receiving his call tonight and his desire to cancel every other appointment biases me. He is following her to New Orleans. This burns like a failure.

“There is something broken, but I can’t put my finger on it. Any colleague would laugh at me for keeping him in therapy for so many years without a diagnosis. But an aura permeates from him. I sense it, I can’t get it out, and now, my pity, I might not be the one to fix it.”

***

It had been weird for Hermann to listen to the whole summary of his own therapy. Even more to discover the notes and comments of the doctor that had followed him. How little he had understood. But Valentine had asked him to close his ties. She never said to listen to the cassettes, and he suspected she would not like it, but so it was. He was certain she would discover it somehow. She had always been able to.

It was night again, though, and as he threw everything he had collected in a garbage bag in his trunk, some dull misery took hold of his heart.

***

The drive from Houma to New Orleans had been fast. Faster than he had thought. He sighed. It might have been worth enjoying the breeze of the night, refreshing, for once, in a place always so muggy. There was music in the air that night, for sure. Something important was coming.

Why did she send him on this mission?

It could even be something Doctor Millard knew or the recordings in the garbage bag. He wouldn’t ask. Valentine would never give him a straight answer, anyhow.

She had bossed him around for the good part of two decades. Scared of a danger that never arrived. New Orleans, the old city, was safer than Houma. Safer from what, he didn’t know. Hermann sighed. One day, if this kept going as it was, they would have to move somewhere else.

When he arrived in New Orleans, he took the bag from his trunk and threw it on the side of the street. He then took a tank of gasoline from the trunk and poured half of the liquid on the bag, and with the rest, he created a path running from the bag to a point a few meters away and went back to leave the tank, still one-third full, near the bag.

Hermann took out his lighter. It was a good lighter, one of those that keep the flame when left open. He sighed again and threw it on the gasoline path. Everything was done according to the instructions he had received.

Now, he could drive to her without interruptions, hoping Valentine had something less burdensome for him to do this time.

***

Hermann had been away just for a few days, but now, the periodic flashes of the streetlamps as he drove into town played the rhythm of his welcome song. He was home.

The excitement had been enough to awaken the wolf and his sharpened senses. His foot pushed on the accelerator more than he would have wanted.

He was hungry.

It hadn’t taken Hermann too much time to accept that the wolf that lived within him needed an offer from time to time. In fact, it wasn’t much of a price to pay for his immortality and the benefits that derived from it. At first, by the way Valentine kept referring to it, he thought she had turned him into some sort of werewolf, but then he realized how much less literal this whole wolf thing was.

At the same time, the wolf was him and was something else. It was like carrying a silent passenger within him. A bundle of instincts that communicated in growls and winces. An exaggerated caricature of himself, furious when he was angry, frightened when he was scared, voracious when he was hungry. It was no more humiliating than eating or defecating.

Mortals had become disgusting to his eyes in most ways, and he could not stop the thought of their nasty habits from crossing his mind. His stomach twitched as he pictured their hands grabbing food and bringing it to their mouths, hands dirtied by the grease of the food they ingurgitated every day while humors drooled out of their lips.

Their flat teeth crunched and melted everything, reducing it to what they themselves, disgusted, would have called vomit had it moved in the opposite direction. Their guts contorted in the desperate attempt to compress, squeeze, and extract something good out of that mire. The idea of how all of that would end horrified him: the vilest act, when naked, vulnerable, and bent on themselves, they would expel the result of their intestines’ work between sighs and grunts.

It was nauseating.

His sight clouded at the idea, and he slowed down just to speed up again a moment later. He had to stop for dinner as soon as he arrived in town. This was the deal. He would feed blood and meat to the wolf, and this would give him enough time to reach his wildest dreams. He had signed the contract long before.

It was an easy protocol. He just needed to find some cheap drinks and someone stupid enough that his car could mesmerize them. At that point, he would take out enough blood to keep going for one night, perhaps avoiding killing his victim, shower them in whatever bad alcohol he had at the back of his trunk, and drop them near a dumpster. Wolf fed and mission accomplished.

Yes, once again, mission accomplished.

***

Hermann entertained the idea of not going to Valentine right away, but he had to talk with her about his little adventure out of town, and either he would go to her, or Valentine would find him, anyhow.

She had made the little theater in Vieux Carré her own, perhaps because the buildings with their old European style and the French café at the corner fed the longing for her old life in Paris. Walking through the Creole areas of town to land in the French district, Herman tried to imagine Valentine’s life in Paris.

He smiled, thinking the red walls of Vieux Carré and its red brick roads were hints that the woman had left for him. Her Old-World origins gave her the freedom to take on an entire district without turning up anyone’s nose. Vieux Carré was Valentine Duchamp’s domain, and every nightcrawler in New Orleans acknowledged it.

She lived there, straight in his brain, as he walked around those old streets, and the thoughts of Valentine walked with him until he reached the theater.

It was late at night and the streets around the theater were deserted. The building was closed at that hour, but Valentine loved spending time there in activities that reminded him she might be a bit mad. The theater would have been empty and the stage silent if it were not for the dirge that kept repeating itself. It would have been hard for a mortal to move around in that darkness, but Hermann’s eyes allowed him to walk around using only the faint light filtering through the windows.

Someone dear to him sang the dirge, a failed lullaby, in honor of a teddy bear left on the ground. Since the first time he saw Valentine, she had struck him, not much for her beauty because, to be clear, she had never been beautiful, but because her innocent blue eyes trapped between voluminous scarves and blonde locks made her somehow attractive.

Those eyes looked at the world in awe, unaware of what to expect from the future and trusting everybody. Those eyes were her biggest lie, her most dangerous hoax as they hid her true nature.

Hermann came close to the woman, and running a hand through his hair, he reached into the inner pocket of his coat to take out a cigarette. He looked at her for a while, but as soon as he was about to raise his hand to greet her, Valentine stopped singing and stared at him with motionless eyes, her head tilted, and a curious smile on her face.

“Hermann, my dear, welcome home. You have mail,” she said without standing from the ground where she sat. She then took an envelope from under her bulky sweater and threw it at him. “Read!”

No sender and not opened yet. On the envelope, only the recipient’s name: Valentine Duchamp. “For me, all right,” he said.

“You need to leave tonight,” she said, her eyes still fixed on him.

He glanced at the letter again. And her name wasn’t on the envelope anymore. Instead, it read Hermann Walker.

The man took another puff of his cigarette, the best thing to calm his nerves. “I imagined I’d spend some time in New Orleans.”

She glanced again at the teddy bear and grasped it to rock it like a child. “I need you in Paris.”

“You do? Stop acting like a child then!” he said and bit his lip.

He expected anger, but Valentine smiled. “You chose to see me like this. Of all the ways you can choose to see me, you keep picking this one. It’s kind of inappropriate if you ask me, but what kind of comfort are you seeking, my dear?” she asked, tilting her head to catch his eyes.

“I … How much time before I go?” Hermann asked. It would be useless to debate her if she had decided already.

“Mr. Walker,” said the voice of one of her servants from behind the stage. The man emerged from the shadows. “I’ve organized everything according to the instructions. Nobody will annoy you during your trip, sir.”

Hermann didn’t want to listen to him. Did she have to send him over like this? On a whim? Hermann took another whiff, flipping the envelope around with his fingers while he followed the servant. But before he could turn to say goodbye, Valentine wrapped him in a hug behind his back. She was warm, and her hair tickled his neck.

“Be careful, please,” she whispered.

When he turned, the theater was empty. Nobody was there beyond him, the servant, and a teddy bear on the floor. An old radio sat on the stage playing a lullaby. Hermann could not resist a smile. He needed to be in Paris.

***

Evidence J-0074 to the investigation I-7242

Extract from Arnaud Demeure’s journal

5 August 1259

“Who is she?” I asked the others who, like me, watched the schoolmistresses chasing a blonde girl away from the courtyard of the orphanage. She was one or two years older than me.

“A gypsy,” one said. “She comes along now and then to sell her junk, but really, she comes to kidnap the little ones. She lives with a witch out of town, and I bet they eat babies for breakfast.”

The others laughed.

“Does she not already look a bit like a witch herself?” another asked.

I didn’t know about them, but she was, to me, the most beautiful thing I had ever seen.